Many in the media and on the Internet have speculated about what really happened on 27 March 1999. These stories range from absurd guesses to ones that have a certain level of reality. Few publications in the English language in the years after the NATO aggression have been written, but they were written with a one-sided approach. Until recently, these publications and articles were taken for granted, but the truth was finally revealed 20 years after the fact, with the first book published in English and written from Serbian sources.

This article, published on the event’s 25th anniversary, is the final and the only real story of what happened that night from the perspective of the Serbian side

27 March 1999

The war has been waging for 3 nights. NATO bombers use Hungarian and Romanian air space as a transit and staging area to attack the northern part of Yugoslavia (mainly targets around Belgrade, Novi Sad, and Pancevo, including the largest air force base in Batajnica. Flying over Romania, in proximity to the eastern Yugoslav border, provides them with a short distance and several minutes of flight to the targets and relative security because Yugoslav air defense does not engage any target outside its own airspace. That evening, a US F-117A, which had taken off from the Aviano base, was on approach to attack the Strazevica underground command and communication center near Belgrade (object 909).

In its way stood the 3rd battalion from the 250th Air Defence Brigade.

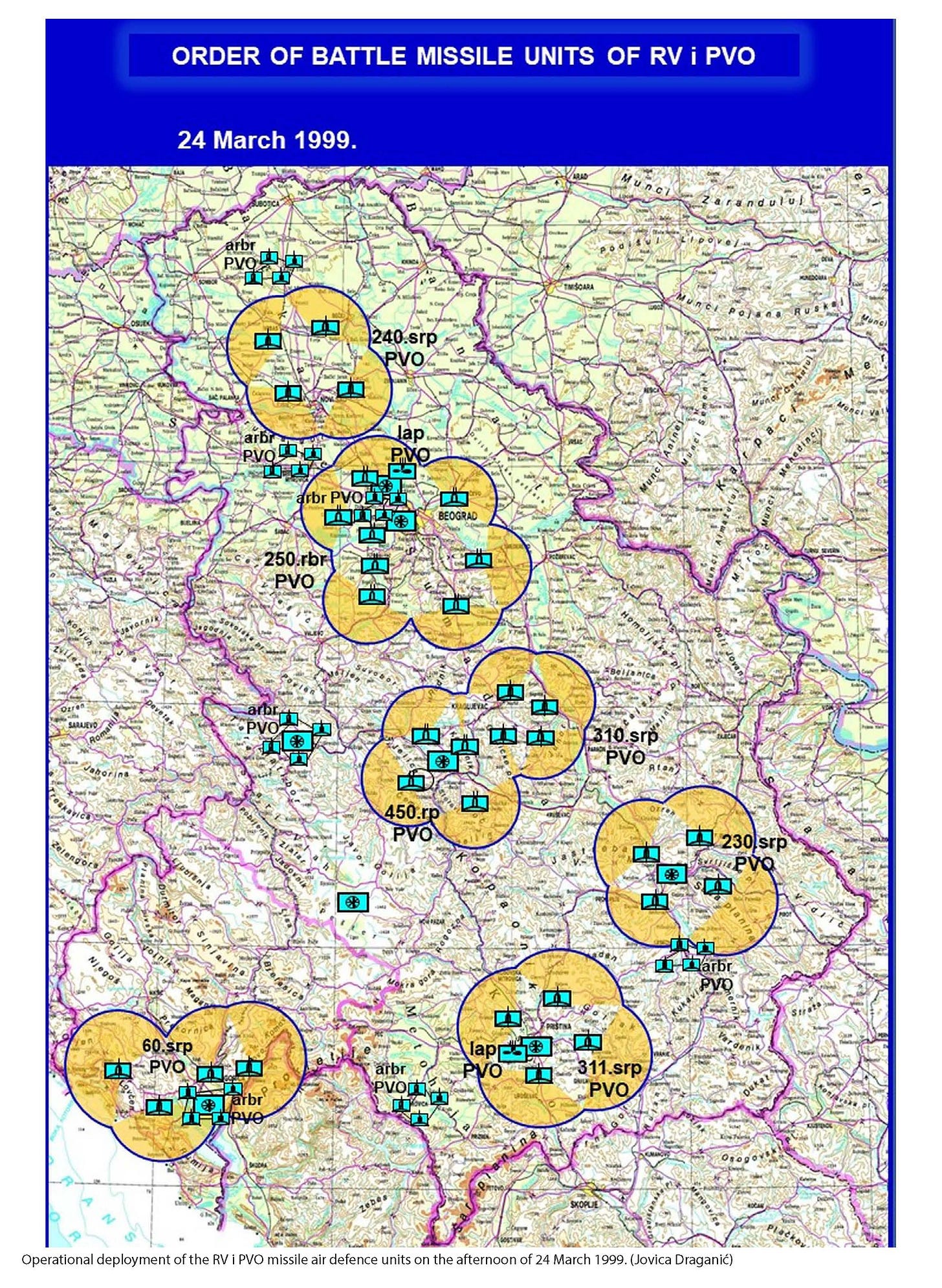

Yugoslavian air defense at that time consisted of old Soviet-made equipment that was not capable of covering the whole territory. The reader can see from the following map how scarce the AD was and how much freedom of attack NATO aircraft “enjoyed” over Yugoslavia.

Unusual usual day

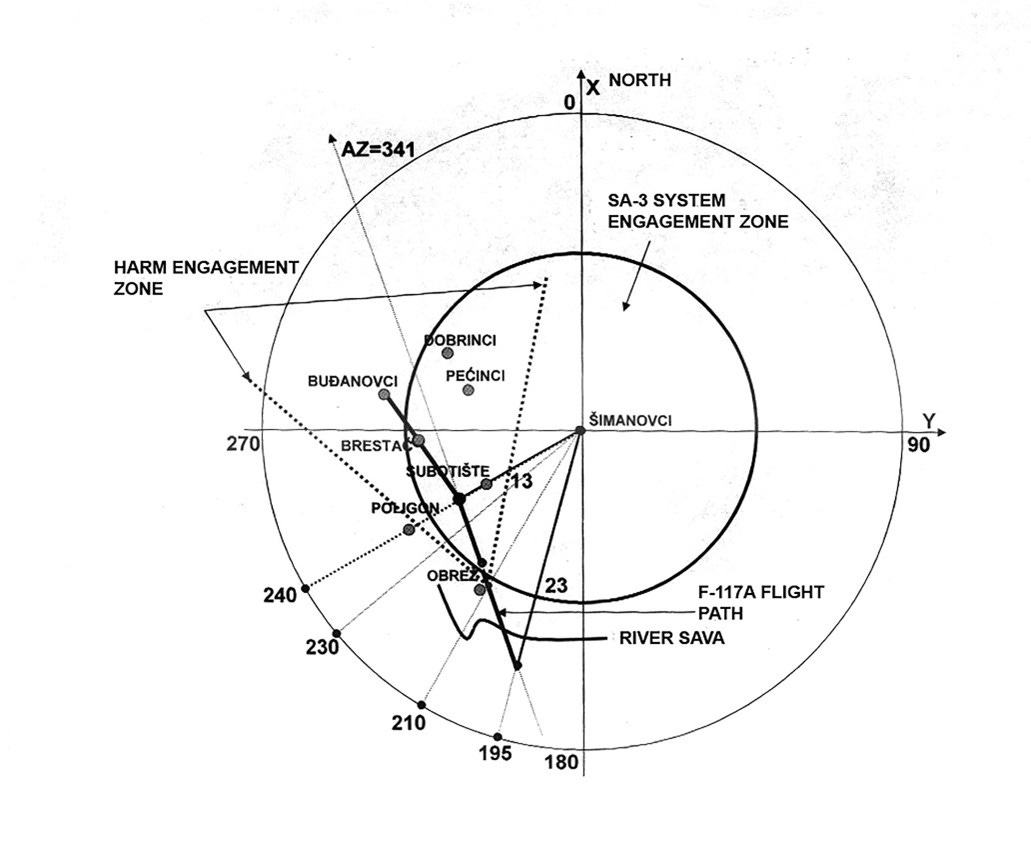

The daily ‘routine’ was established. Combat shift changes were regular – in six-hour intervals. The 3rd battalion had two combat shifts: Lt. Col. Dani (as a battalion commander) was in charge of the first, and Lt. Col. Anicic (battalion deputy commander) was in charge of the second. The 250th Brigade Operation Center ordered Lt. Col. Anicic to go to the three decoy locations and perform the radar imitator emissions from 14:00 until 20:00. The idea of brigade HQ was to use the radar imitator to simulate the work of tracking and engagement radar. Brigade HQ was sure that NATO ELINT airplanes would pick up emissions and plot the locations. Moving from one location to another and emitting simulated radar emissions at twenty-minute intervals may create an impression of more tracking radars and, thus, more missile batteries present. That was a classic military deception attempt. If the decoys worked as planned, NATO would record all positions and plot them as SAM sites. They would then be flagged in the flight computers as potentially dangerous zones to be avoided. As the real battalion was in complete radio and radar emission silence, it would wait in ambush for an unsuspecting aircraft to appear.

The plan was to use location No. 1 Subotiste and perform twenty-minute emissions on azimuth 270, then move to location No. 2 Pecinci and perform the same task on azimuth 270 for the same time, then move to location No. 3, Dobrinci and perform the emission on azimuth 230. The task would be executed by 20:00, then the radar imitator would be positioned in the vicinity of the battalion and used as a decoy. Lt. Col. Anicic was scheduled to take the combat shift at 18:00, so the time frame was tight to perform all assigned tasks and get to the combat position on time to take over the shift.

One interesting detail regarding this task is why the brigade ordered a high-ranking officer and battalion deputy commander to do a task that can be executed by NCOs. Lo. Col. Anicic was familiar with the assigned area, and the estimate was that it would be easier to lead the group. It shall be mentioned that the radar emission imitator crew just had training with the device but still needed some practical field experience.

A radar emission imitator emits electromagnetic energy at the same frequencies and wavelengths as an engagement and fire control radar used in missile guidance. There is a high probability that these false radar signals will be picked up by ELINT aircraft and fighter-bombers carrying anti-radiation missiles such as HARM. Missiles are liable to fly towards the decoy instead of towards the real radar.

In the meantime, at 18:00, Lt. Col. Anicic’s combat crew started their evening shift. Lt. Col. Dani continued his previous shift as commander until the return of Anicic. Major Boris Stoimenov took over the position of the deputy combat crew commander with the new crew. Combat readiness was No. 3, which is the lowest, usually when there is no activity in the air. The crew is on 15-minute readiness. During the previous shift, it was noted that there was a problem with the P-18 radar receiver because there was no picture on the screen below 60-70 km. After a conversation with the commander, Major Stoimenov, who was also a battalion technical officer, went to the radar van and, together with the radar crew, tried to fix the problem. There was an issue between the parameters of the signal and cluster. Major Stoimenov told the commander that the repair might take about ninety minutes. Sergeant Ljubenkovic and Major Stoimenov worked on the equipment without turning on a high voltage and radar emission. After the repair, Major Stoimenov requested Lieutenant Colonel Dani to turn on P-18 for final adjustment and tune-up. He was back in UNK (missile guidance station) at 19:20 and reported to Dani that the radar was ready but that the receiver needed to be adjusted. Because the probable attack had been expected from the west, the radar antenna was positioned on azimuth 90, and emission was turned on. After the final tune-up, the high voltage was turned off.

It should be mentioned that there was no previous modification on the P-18 radar or any hardware upgrades that would allow the old radar to detect stealth aircraft. This story was placed in the Serbian media as a form of propaganda and was readily picked up by Western media, but nothing of that is true. P-18 is capable of detecting and tracking stealth aircraft without modifications because it operates in the wavelengths in which F-117 or any other stealth aircraft are not "immune" to detection.

The situation was quiet, and nothing was on the radar screens. In the first few days, the air raid alarm usually sounded around 20:00. That was the local time when NATO airplanes approached designated targets and were picked up by surveillance radars and visual observation pickets.

Brigade command ordered the crew into combat readiness No. 1 around 19:35. The missile guidance station (StVR in local terminology) and radar P-18 were turned on, and the crew performed final checks. In combat readiness No. 1, the crew was ready to engage a target at any moment.

Combat procedure requires that the crew be in constant communication with the brigade command center. The commander is in front of the P-18 screen (VIKO). Beside him sits the deputy commander, and both can see the radar screen. Every sweep on the radar screen showed airplanes in the air…but they were far away.

The UNK of S-125M is cramped; the designers' last concern was the crew's comfort. The chairs are anything but comfortable, the humming noise from electrical equipment is rather loud, and the air conditioning is barely sufficient to move the stale air. The smell of uniforms, muddy boots, and unwashed bodies is not pleasant. In that space, six officers, NCOs, and enlisted men performed their tasks.

23 Seconds

A missile battalion combat crew is a team. Every member plays his part, and all roles are critical. If anyone doesn’t do his duty, the whole team will fail… and in war, that can be fatal.

The life of a combat crew during an engagement is measured in seconds. That is how much time is available to fulfill the mission or die trying. In ordinary life, seconds do not mean much, but for missile operators, that is the difference between bringing down their target or being shredded to pieces by an anti-radiation missile or laser bomb.

On the evening of 27 March, the crew consisted of Lieutenant Colonel Dani Zoltan, commander, responsible for all in the UNK; Lieutenant Colonel Djordje Anicic, battalion deputy commander and XO and assigned shift commander, responsible for all activities out of the UNK such as power supply, radar, communication, signals etc.; Major Boris Stoimenov, until the arrival of Lieutenant Colonel Anicic deputy crew commander; Captain I Class, Senad Muminovic, fire control officer; Sub Lieutenant Darko Nikolic, battery commander; Senior Sergeant Dragan Matic, manual tracking operator on F2; Sergeant Dejan Tiosavljevic, manual tracking operator on F1; private Davor Blozic, clerk and manual plotting board operator. Besides the combat crew in UNK, the detached truck with power source pack unit (Sen. Sergeant Djordje Maletic and Private Sead Ljajic) and P-18 early warning and surveillance radar station (Sergeant Vladimir Ljubenkovic and Private Vladimir Radovanovic) also played a critical role.

What was unusual that evening was that in the moment of engagement, there were two commanders in the UNK. Combat rules allow only one commander, but in war circumstances, it may be different. Lt. Col. Anicic returned to his post at 20:30. At that moment, there was no combat engagement, but the missiles were at Readiness No. 1 on the ramps ready for launch, but there was no combat readiness in the station, which is very unusual (why we’ll see in the next section). The night was clear. Moonlight reflected on the stand-by missiles and their launchers.

The situation started to change when Colonel Dragan Stanković (250th AD Brigade Deputy Commander) ordered missile battalions to enter combat readiness based on the information about the grouping of the NATO planes north of Belgrade. 3rd battalion went to Readiness No. 1 at 20:15

When Anicic entered the UNK, Dani was leaning on the electronic control blocks by VIKO, apparently having a rest. Major Stoimenov got up and moved behind the fire control officer so that Anicic could take the seat (as a senior officer and his shift commander). Anicic took over the headset with the microphone, which is used to contact the brigade operation center. Technically, as Anicic entered the UNK, he was shift commander, taking over the position with his previous shift. As Lieutenant Colonel Dani was about to leave they exchanged thoughts and information of the day, reflecting on activities in the battalion and the individual tasks. Lt. Col. Dani sat in the shift commander’s place until formal duty handover, and Lt. Col. Anicic sat in the deputy commander’s chair. When Dani left a few minutes later, Major Stoimenov would take the position of deputy commander. It was a routine procedure for the previous and new shift commanders to exchange information during the duty handover. There was no formal military reporting to each other, rather it was a conversation.

While the two officers talked about the afternoon situation and performed tasks, Lt. Col. Anicic faced the P-18 screen and saw clearly what was happening on the radar screen. Lieutenant Colonel Dani was turned sideways, not facing the screen this time. The P-18 radar screen on VIKO showed that there were airplanes in the air, but out of range and on different azimuths, somewhere in the vicinity of Belgrade. The radar imitator that Anicic brought back from the field was not yet connected.

In the meantime, the F-117A had been targeting the underground complex at Strazevica with two GBU-10 Paveway PGMs at 2036 hours. The 3rd Missile Battalion received the first identification of the approaching aircraft from radio amateurs. It should be stated here that neither the missile battalion nor anyone else had any idea about the particular type of plane. For them, it was only a target.

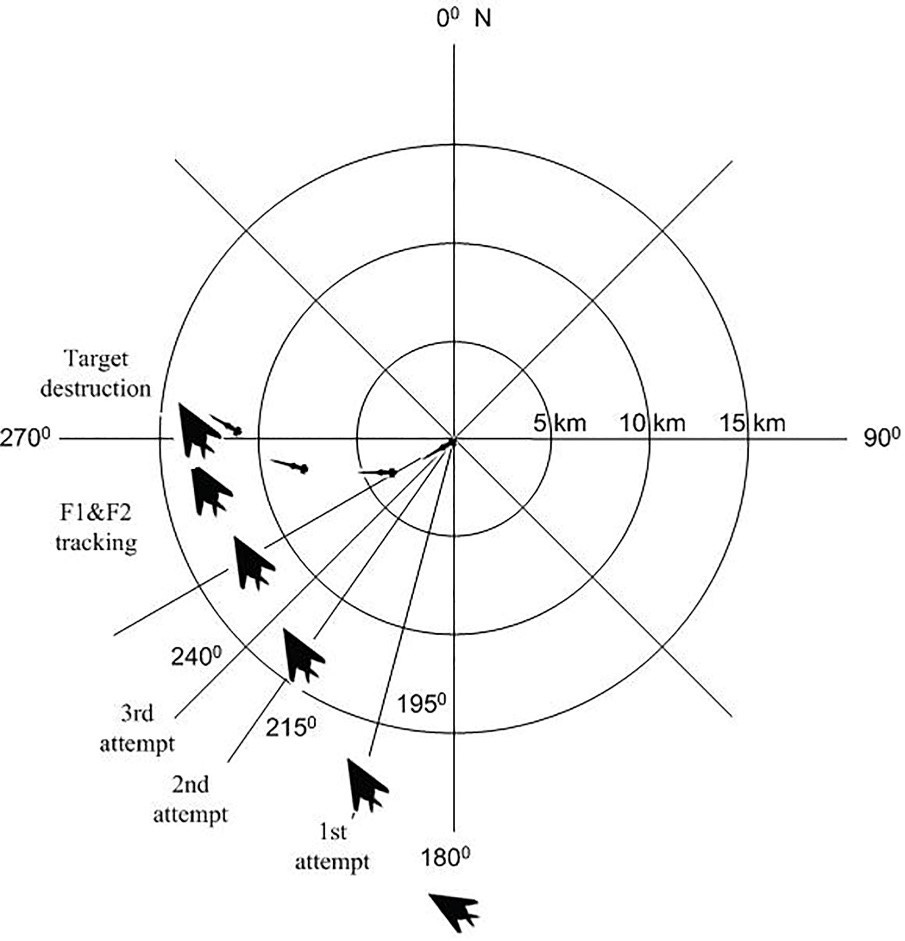

While exchanging thoughts of the day, suddenly, the surveillance radar showed three blips at azimuth 195, at a distance of 23 km. Anicic followed three more sweeps when he saw that one target was 17-18 km from the radar. He then informed Dani about the blip on the radar screen.

‘Dani, this guy is coming toward us.’

Dani quickly looked at the screen. The next sweep showed that the blip was 14-15 km away and approaching. After two more radar sweeps, Lieutenant Colonel Dani ordered, ‘Azimuth 210!… Search!’

Sub-Lieutenant Nikolic, the battery commander, started to turn the control wheels on his UK-31 plan position indicator and the start zone (part of UK60 station) in an attempt to guide the missile guidance officer by azimuth and elevation: ‘To the left…to the left stop!...right…up…up…up, stop! Antenna!’

At this moment, the fire control radar is turned on. The cat-and-mouse game starts…Whoever is faster and more agile wins!

The battery commander guided the fire control officer to the target. Captain Muminovic, the fire control officer on his UK-32 station, frantically turned three wheels at the same time, trying to find a target on his two screens. His first attempt was not successful. He couldn’t mark up the target (bring the blip into the crosshair on his two screens), and he handed it over to the manual tracking operators. The target had high angular velocity and was maneuvering, which might have been why the operators were not able to start tracking. The fire control radar emission seemed too long. What the battery commander thought was that the target had most likely got a warning signal in his cockpit that he was illuminated by the engagement and fire control radar.

The time between target detection, fire solution acquisition, firing command issued, missile launch, and target interception could not be more than 27 seconds. Any longer, and the station would be hit by an anti-radiation missile. That was the time needed for an AGM-88 HARM to fly from the launching airplane to the radar. Tension was in the air…

As the fire-control radar emission was ten seconds long, Lieutenant Colonel Anicic ordered: ‘Stop searching! Equivalent!’

Sub-Lieutenant Nikolic didn’t hear that command, or he might have been confused by two combat shift commanders issuing orders. Lieutenant Colonel Anicic ordered much louder: ‘Get—the—High—down!!!’ and Nikolic immediately turned it off and reported: ‘High—off!’

The guiding station was saturated with humming noises from the electrical equipment, the clicking of switches and wheels, and loud commands and crew responses. This time, the guiding officer could see the target on both screens. Metal wheels clicked… Captain Muminovic pushed the wheels hard forward to get the target into the crosshairs of his two markers, but after a few attempts, he was not able to. When the target is in the crosshairs of both markers, he can transfer it to the manual tracking operators on F1 and F2. The second attempt was when the target was approximately 14 km away.

Again, the radar emission was way too long, and Anicic commanded: ‘Stop searching! Equivalent!!!

A few seconds later – the next attempt. Lieutenant Colonel Dani ordered: ‘Azimuth 230!... Search!’

Nikolic responded promptly: ‘Equivalent!’

A few seconds later, Dani ordered: ‘Azimuth 240! Search!’

The third attempt was when it was 12 km away.

A couple of seconds later, the guidance officer found the target, and it was clear that it was maneuvering. More clicking of wheels and the target was escaping. Radar emission was 5-6 seconds long and Lieutenant Colonel Anicic said to his commander: ‘Dani, be careful, we don’t want them to screw us.’

The reason for this concern was that airplanes may use decoys, in some cases towed decoys, which represent a large reflective surface that can confuse radar operators and mask the real target.

It happened during the first Gulf War that Iraqi crews had the decoy target on their radar screens and locked their firing parameters, only to be hit by an anti-radiation missile fired from the side by one of the fighter-bombers equipped with HARMs.

Lieutenant Colonel Anicic was about to issue an order to stop searching again because the search time was too long when the operator for manual tracking on F2, Senior Sergeant Matic, vigorously turned his control wheels in an attempt to bring the target in the center of the crosshairs on his screen and yelled, ‘Give it to me! Give it to me!… I have him!!!’

At that moment, Muminovic pushed his wheel forward and handed over the target to the manual tracking operators: ‘Track manually!’

Sergeant Matic locked the target on F2 crosshairs on his UK-33 screen… and that was it... he got him!

The second operator on manual tracking on F1, Sergeant Tiosavljevic, also got the target on his screen markers. The screen reflection was very big. The target was ‘caught,’ and both manual tracking operators had it on their screens.

Captain Muminovic reported that the station had stable tracking, the target was on an approaching path…, and the distance to the target was 13 km. Both F1 and F2 operators reported stable target tracking. All firing parameters were achieved.

‘Station tracking target… target in approach… distance 13 km!’

The operators reported: ‘F1 manual tracking on!... F2 manual tracking on!’ The battery commander didn’t report target engagement probability, but Lieutenant Colonel Dani still commanded: ‘Destroy the target! Three-point method!... ‘Launch!!!’

Muminovic pushed the start button, and the first missile engine started, blasting off from the launcher.

‘First missile launched! First missile tracking!’ (both F1 and F2 operators manually guided the first missile).

After five seconds, the second missile also blasted. The noise of the launches was so loud that everybody in the surrounding area, including the base camp, heard it. The rocket engine blast blew the gravel beneath the launchers and hit the UNK van like shrapnel.

‘Second missile launched – second missile not tracking!!!’

Both F1 and F2 operators reported stable manual guiding for the first missile. The second missile didn’t acquire the target, and the tracking was lost. The first missile was 5-6 seconds in flight and 10 more seconds to the interception point. The F1 operator reported that the target had a large RCS.

Lt. Col. Anicic rose from his seat and looked over the manual tracking operator’s shoulder: ‘How come it didn’t catch the target?!! Why?!!’

The first missile was on a stable trajectory to the target, but the second lost contact with the station and continued its ballistic trajectory away from the target. Something went wrong with the guidance channel. The crew looked at the last few kilometers before the missile reached the target…then the large flash blips on the missile guiding officer’s screen. The missile reached the target at 20:42…. The target was destroyed…, and the interception was at 8,000 meters altitude. The target was acquired at 6,000 meters. Obviously, the pilot saw the launch or had been warned that he was illuminated by the fire control radar and tried to perform anti-missile maneuvers, but once locked, there was no chance he could avoid being hit. The whole operation lasted about 23 seconds (according to another source, it lasted only 18 seconds). In any case, both times are extremely low.

And that was it. The stealth fighter is downed.

The Invisible Shift - a documentary about the legendary combat shift (with English subtitle):

Part 1

Part 2

The whole downing can be seen in a very good SAM simulator (bear in mind that that simulator is not a game but a realistic S-125 simulator).

Stealth in the mud

This is the story of what really happened on the evening of 27 March 1999. At 8:42, the Nighthawk hit the black fertile soil near the village of Budjanovci.

The pilot ejected and was later rescued. Nobody was seriously harmed… except the pride of the United States Air Force and NATO.

After the downing, there were some speculations about what happened with the wreck.

Engines, canopy, and parts of wings were collected, and most of what was left after the war is now in storage in the Belgrade Airspace Museum. The canopy and one wing are on public display. Some parts were handed over to the Russians and Chinese. Everything was shrouded in secrecy, and there are no officially published documents about this, but it is certain that the Russians got parts interesting to them, and the Chinese also got ‘their share’.

Some of the parts were finished as souvenirs, and others were "repurposed," such as a rooftop for the field toilets (outhouse).

Post downing

According to records from the 280th ELINT Centre, the pilot turned on his ‘beacon’ at 243.000 MHz one minute after ejection. His signal was identified by a British air controller inside the NATO E-3 AWACS (call sign Magic 86). The signal was received by the ABCCC (call sign Moonbeam) and one of the USAF air tankers, which were orbiting in Bosnian airspace. The latter was the closest NATO aircraft to the crash site at the time. The AWACS that also monitored the situation canceled a strike package that was about to enter Yugoslav airspace and ordered four F-16s and two F-15s to organize a CAP in the area around the crash site (air war over Yugoslavia)

Did Serbs Track the Stealth?

USAF officials immediately after the downing came up with multiple theories on how it happened. Some reports mentioned prearranged flight paths and that Serbs somehow found the pattern. Serbian spies tracked the F-117 from its take-off, through Hungary, and during the target approach. Serbian command used optical cables and mobile phones to transfer the information to the specific designated unit that would launch the missiles. One report spoke of a lucky shot, that Serbians randomly fired missiles and scored. Another guessed that Serbs were able to penetrate the radio communications between airplanes and command centers and pinpoint the individual plane location. There was also a report that Serbs are believed to have plugged powerful computers into their air defense radar system that helped to reveal the flight paths from the faint stealth radar signatures; that a Czech company produced the radar system that could pick up electronic emissions from the stealth airplane, but it went bankrupt and Serbia somehow got possession of their ‘Tamara’ systems. This is nonsense and pure fantasy!

For several years, that was one of the ongoing myths; there is some truth, but it was not on the level that was presented. The USAF delegation that visited Serbia in 2005/06 was keen to know the abilities of stealth tracking. Military establishment at that time provided them with some information. They were told about the Serbian unit (280th ELINT Center) and how they were able to intercept some signals (SIGINT) monitoring radio communication, and among these signals were those from the stealth fighters. It was a bit of a slam to the face and a very nasty surprise for the US experts to hear how Serbian ELINT operators managed to track the stealth aircraft while constantly monitoring NATO air communications prior to and during operations. This needs to be clarified further: the stealth pilots mostly obeyed the strict discipline in radio communication, but the other pilots and crews were not so strict. Such comments were mostly made by air refueling crews and pilots who were performing routine combat air patrol missions. Colonel Vujic, who commanded the 280th ELINT Centre during Operation Allied Force, confirmed that they identified a total of 279 F-117A sorties during the whole campaign. They had done so during the evening of 27 March, when at least five F-117 stealth fighters were identified, with the information passed on to the operations center at 19:58. However, this information was not communicated to any of the missile battalions (4).

Another Stealth

The same unit was also able to hit the second stealth jet, which was able to land in Spangdahlem Air Base, Germany.

According to some reports, it is possible that the third stealth was also hit, but for now, there are no official records or confirmation.

The second confirmation took 20 years to be acknowledged, and the third hit may also be confirmed after some time.

Source:

M. Mihajlovic, Dj. Anicic: Shooting Down the Stealth Fighter: Eyewitness Account from Those Who Were There

M. Mihajlovic, Dj. Anicic: Missileers against the stealth: The First Downing of the Stealth Fighter in History

Dj. Anicic: The Shift: Air Defence Missile Officer War Diary

B. Dimitrijevic, J. Draganic: Air war over Yugoslavia, Part 1 and Part 2

If you like the article (and much more articles regarding military subjects will come) you can buy me a coffee:

https://www.buymeacoffee.com/mmihajloviW

[i] Edited by Piquet (EditPiquet@gmail.com)

Well, I suppose that now that the cat is out of the bag, there's no real need to keep guarding the secrets on detecting stealth aircraft. :) I forgot the details of how I learned about this (I think I read a hint on some forum and then figured out the "last mile" myself), but basically - radiowaves reflect off (AKA interact with) electrically conductive lines that are approximately the size of their waves. So modern radars which operate on GHz interact with metal surfaces approximately 0.1 to 0.01 meters in size. This is why stealth airplanes have a broken-up shape: it prevents them from having a flat surface of several centimeters in length, which would give a good reflection. But a VHF/UHF radar emits waves whose lenghts are 1 meter or more in length. At those lengths, it doesn't matter how broken up the airplane surface is, it's all flat for the wave. The downside is that it also sees all kinds of gunk above and beyond airplanes, such as clouds. It also has lower spacial resolution, needs bigger antennas etc etc.

Funny story: some years/a decade ago, Australia built an early warning radar. At the time, they said the radar picks up stealth airplanes as well as any other and they explained this by saying the waves reflect off the ionosphere and "come down on" the airplanes vertically and reflect off the cockpit, and that this is the reason. In reality, the radar operates on HF, with wavelengths 10-100 meters. Thus the entire airplane sits comfortably in a single wave. History doesn't record if Aussies were aware of the wavelength connundrum I explained above. :)

One other comment: considering how non-automated and BLOODY SLOW the entire operation was, it's a wonder they shot down anything at all. It's also amazing how those radars weren't moveable, to evade the HARM. It also shows how sloppy and disorganized NATO was. If NATO were serious, they would have had one or two Nighthawks trailing the attack craft, specifically to deter air defence. I think they started doing that after they lost their first airplane. But the word on the street is they used ordinary non-stealthy airplanes in that role.

All in all, shit equipment, I'm amazed our guys shot down anything at all. The stuff they have now is a little better but it's still shit. What we need is some 5-10 S-400, for a start. Maybe some nukes on ballistic missiles as well (to kill Aviano). Anything less is just asking for trouble.

Thank you for this riveting account of the tense and rapid action inside the cramped Serbian Air Defense unit, fighting time, second by second, to kill or be killed, Mike.