"Something Big" Was in the Air: B-2 Over Yugoslavia [i]

The B-2As' combat missions over Yugoslavia

Back in 1999, the B-2A was regarded as the pinnacle of U.S. bombing capability, a predator in the sky capable of accomplishing missions that would have required hundreds of conventional bombers.

As circumstances unfolded, the B-2A drew its first blood in the bombing of a small European country, a display meant to project the power and "invincibility" of U.S. and NATO military might.

More than a quarter of a century later, even the most committed supporters of NATO's ongoing interventions have come to recognize that the entire operation was built on a foundation of misinformation, lies that became routine among the political class. The military, in turn, was left with little choice but to follow orders and carry out the will of those in power.

As a result, powerful bombers were unleashed in a punitive campaign against an opponent whose air defense systems were significantly behind the times. For war hawks and admirers of the military might that “Uncle Sam” could project, it was a perfect opportunity to showcase that power.

This article will explore what happened, and why, even before the end of hostilities, these mighty aircraft abruptly ceased operations, despite the fact that numerous targets remained and the skies over Yugoslavia were reportedly just as dangerous as they were on the first day of the aggression, as noted by some Western media outlets.

“First Blood”

For those interested in the development of the B-2 and its combat engagement related to Iran, these topics have already been addressed in this Substack. According to U.S. sources, which were widely cited:

…” Exactly 51 pilots flew the B-2 in combat. Most of them flew one mission; a handful flew two, and one pilot flew three times. The B-2 mission-capable rate during [Operation] Allied Force, not counting low-observable maintenance, averaged about 75 percent. When such maintenance is included, the figure is about 60 percent. However, not a single B-2 mission started late, and only one airplane had to abort its mission for an in-flight mechanical problem. Each B-2 could—and, in some cases, did—attack 16 targets in 16 different locations per mission. Pilots reported they were apparently never detected…”

It all sounds quite remarkable, almost like a used car salesman trying to convince you to pay far more than what the vehicle is actually worth.

What readers will rarely hear from Western sources is the other side of the story. Few mention that, in Yugoslavia, there were individuals who had studied the B-2 and F-117 extensively, using not only all publicly available information but also other, more sensitive sources. In addition to open-source intelligence, classified materials and detailed calculations were reportedly analyzed. The science of electromagnetic scattering was not a discipline exclusive to Lockheed Martin or Northrop; expertise existed elsewhere as well.

The claim that the B-2 was never detected is, quite simply, a myth. In fact, it can be viewed as a typical example of the kind of overconfidence and misinformation often found within both the civilian and military branches of the U.S. government, to put it politely.

Handmade calculations, based on equations and manually drawn diagrams, were just one of the sources used in the analysis. The bottom line, according to those findings, was that the B-2 had a larger radar cross-section (RCS) than the F-117. This assessment was later supported by several other sources, including acknowledgments from U.S. defense-related publications.

Estimates performed by the author in 1998 and early 1999 indicated that the B-2 could be detected by metric-band radar across all flight regimes at distances exceeding 25 km, as well as being locked on by fire control radars operating in centimetric bands. At the time, Serbia’s air defense systems were generations behind the best that the U.S. and NATO had to offer. There were no illusions about achieving air superiority or inflicting significant damage. The overriding priority was survival—preserving both personnel and equipment wherever possible.

The B-2 bombers flew all the way from Whiteman Air Force Base, delivered their ordnance over Yugoslavia, and returned home, a pattern repeated throughout April and early May of 1999. However, on May 21, all combat operations involving the B-2 abruptly ceased.

For anyone reviewing the news from that period, it's clear that many viable targets still remained across Yugoslavia, targets that, by all standards, would have justified the deployment of such a sophisticated platform. One U.S. general even remarked that the skies over Yugoslavia were as dangerous on the last day of the war as they were on the first.

So, the question remains: why did the B-2s suddenly withdraw from combat? What changed on or around May 20 that led to their early exit, despite the continued strategic value they could have offered?

“Something big was in the air” - through the eyes of the air defense combat shift

Somewhere in the plains of northwestern Serbia, a missile battalion lay in wait at its combat position. By that time, the battalion had already recorded two confirmed kills and one unconfirmed, the latter believed to be a hit on an F-117 that managed to limp back to its base in Germany. This 3rd Battalion was a seasoned combat unit, one of the few remaining in active air defense. Despite enduring multiple attacks, it had not lost a single member or piece of equipment, except for one induction field phone that was accidentally left behind at a former combat position.

Lieutenant Colonel Aničić and his crew began their afternoon shift at 16:00 on 19 May 1999. That same day, Russian envoy Viktor Chernomyrdin was visiting Belgrade for high-level talks with President Slobodan Milošević regarding the ongoing conflict. All signs pointed to a relatively quiet night.

At around 22:30, Chernomyrdin departed. Shortly after, at 22:50, the radar crew was placed on Readiness Level 2, indicating a lowered state of alert and no immediate threat. Due to the heat inside the UNK (missile guidance station) cabin, the crew removed their flak jackets and helmets.

Still, it struck the shift commander as odd. Just the day before, the unit had operated at Readiness Level 1, the highest state of alert, in anticipation of a NATO strike. The sudden downgrade in alert level, despite no meaningful change in threat assessment, seemed suspicious.

In the days leading up to the event, the battalion faced considerable difficulty preparing combat positions due to heavy rain and deep mud. That night, the unit remained on Readiness Level 2—an unusual state given the overall threat level. The combat crew took advantage of the lower alert to rest briefly.

Suddenly, at 23:00, the brigade command post issued a sharp order: shift to Readiness Level 1. The crew immediately sprang into action, taking up their positions and preparing for engagement. Lieutenant Colonel Aničić ordered the P-18 surveillance radar activated.

Moments later, the VIKO display lit up—multiple targets appeared at just 10 to 12 kilometers, alarmingly close. A large-scale attack was clearly underway.

However, the fire control radar was not yet fully operational. The aging technology required a warm-up period before becoming combat-ready. Due to this delay, the battalion was unable to engage the first wave of targets, known as the "first ring." The second ring, located approximately 25 kilometers out, became the focus.

As the targets appeared on screen, the radar operators and commanders quickly recognized familiar patterns. By this point in the war, they had developed an instinct for interpreting radar signatures: they knew what a real aircraft looked like, how a towed decoy behaved, and how a radar decoy registered on the radar. But this time, a new kind of blip appeared, triangular, unlike anything they had seen before.

The operators carefully studied the radar returns. By this stage in the war, they had become adept at identifying patterns, knowing how a real aircraft appeared on screen, how a towed decoy looked, and how a radar decoy behaved. But now, a new and unfamiliar blip appeared. It was triangular…

Let’s now step back and explain those famous blips on the radar screen:

One thing was certain: the crew were veterans, highly skilled at distinguishing what was in the air simply by analyzing the size and parameters of radar blips. It is important to note that the P-18 VIKO radar used an analog display, similar to an oscilloscope screen, where raw radar data appeared directly. In other words, the size of a blip generally corresponded to the physical size of the target.

The venerable P-18 radar, as used by the Yugoslav forces, lacked advanced filtering capabilities, meaning operators relied heavily on their experience and intuition to interpret the signals accurately.

One of the few significant drawbacks of the interim and later generations of surface-to-air missile systems compared to second-generation systems—such as the S-75 (SA-2), S-125 (SA-3), 2K11 (SA-4), and 2K12 (SA-6)—is the loss of raw, real-time radar data display. These newer systems prioritize processed radar intelligence (RADINT) information over the direct, unfiltered radar data traditionally shown to operators.

Simply put, operators of systems like Osa-AKM (SA-8), Tor (SA-15), Buk (SA-11), and S-300 (SA-10) cannot distinguish aircraft types, such as an An-2, An-26, or An-124, by simply looking at the radar indicator, as operators of the P-18M (surveillance and tracking) or SNR-125 (fire control and missile guidance) system could.

The SNR-125 radar display presents raw data, where the size of the marker corresponds to the size of the reflected signal. For example, a smaller marker might represent an An-2, while a larger marker indicates a bigger aircraft.

For example:

An S-sized marker would represent a small aircraft, such as the An-2.

An L-sized marker would correspond to a medium-sized plane such as the An-24.

An XXL-sized marker would indicate a very large aircraft, like the An-224.

That said, while the crew cannot identify the exact type of aircraft based solely on the size of the radar blip, they can still obtain reasonably reliable information to differentiate between fighters, bombers, or decoys. However, this task is not as simple as it may sound, since other factors, such as speed, altitude, and flight trajectory, must also be taken into account.

In short, an operator with six or more years of hands-on experience with the system can, with a certain degree of probability, make an informed assessment about what type of object is in the air, but not with 100% certainty.

Identification becomes significantly more difficult when stealth aircraft are airborne, especially when considering the various forms of electronic jamming that may be deployed against the radar system.

To the radar operators, any blip on the screen represents a potential target until proven otherwise.

Inside the UNK cabin, tension spiked.

“Azimuth 180… Search!” Aničić commanded, initiating a radar sweep along the 180-degree axis.

A new target appeared—17 to 18 kilometers away, closing fast.

“High voltage – Up!”

“Antenna!”

The target was now at 15–16 km.

Within seconds, missile guidance officer Janković located the target. With subtle adjustments to the azimuth and elevation wheels, the blip was locked in the crosshairs. The target began maneuvering—it had likely detected the radar emission and realized it was being painted by fire control radar.

A single click pushed forward toward the radar station, passing control to the manual tracking operators, who acquired the target on their F1 and F2 scopes.

Seconds later, Aničić gave the order:

“Destroy target with two missiles! Three-point guidance!”

A loud hiss, the ignition of booster motors—then launch. The first missile roared off the rail. Five seconds later, the second missile followed.

Janković called out parameters: altitude, speed… The first missile, Tanja, had acquired the target. The second, Ivana, also locked on. Guidance was nominal on both channels. The distance to the target: 14 km. It was textbook execution.

Suddenly, the F1 tracking operator shouted:

“What the f—?! What the f— is this?!”

The blip on the screen was enormous—it took up nearly the entire display.

The first missile exploded near the target, followed by the second at 13 km, azimuth 180 degrees. A bright explosion lit the sky.

“Target hit—both missiles!” the operator confirmed.

“Take the high down! Equivalent!” Aničić ordered.

Meanwhile, the next shift, waiting outside the UNK, knocked on the van door. It was just after midnight. With a full engagement in progress, no shift change could occur—a dangerous scenario, as a single well-placed bomb or missile could wipe out both combat crews.

From outside, the second shift witnessed the entire engagement visually: the missile launches and the distant explosion. Nearby Praga anti-aircraft guns also fired their heat-seeking missiles that were mounted on the improvised launcher.

News from brigade HQ followed: helicopters were in the air. Everyone knew—something big had happened. Otherwise, helicopters wouldn’t be airborne in the middle of an engagement.

Aircraft swarmed from three directions. After the launch, the UNK reported a malfunction on the missile ramp. The blast from the high-elevation launch had created a crater beneath the platform, shifting the 13-ton launcher 20 cm from its original position. One of the missiles had even fallen off its beam.

The enemy must have sensed the situation. A major air strike followed from azimuth 205, but the crew couldn’t launch in that direction—it was a forbidden zone, where a blast would damage their own equipment. Despite being one of the strongest attacks since the war began, one launcher was out of action.

From azimuths 300–330 and 150–180, more aircraft approached. Aničić ordered his deputy to activate the radar imitator. Short, precise commands followed. The imitator began emitting brief bursts, quickly switching from target to target. Each radar pulse lasted no more than five seconds before switching to a new source.

To the enemy aircraft, it was unclear whether they were being painted by a real fire control radar or an imitator. While the Low Blow radar illuminated one group, the imitator covered the second, which approached from the forbidden cone. The third group remained uncovered—there simply weren’t enough imitators to go around.

Meanwhile, brigade headquarters called to ask about the engagement and how the radar image appeared on the Low Blow system. They had seen everything on the P-18 surveillance radar, but wanted insight from the fire control radar’s perspective. Aničić delegated the response to the missile guidance officer.

Aničić ordered another search sweep and detected two aircraft at 14–18 km, moving out of range. From the rear, another plane approached, entering the engagement zone at 15 km. There was no time to pursue departing targets—the approaching one became the new focus.

As soon as it was illuminated, the screen flooded with electronic clutter—jamming. The missile guidance officer reported,

“Target lost… can’t see it anymore.”

“Turn off fire control radar,” Aničić ordered.

For the remainder of the night, only radar imitators were used. Though aircraft remained in the air, none entered the engagement envelope.

It was clear—something significant had happened. The sheer number of aircraft and repeated attempts to destroy the site were unlike anything seen before.

At 01:30, the sky finally cleared, and the combat shift ended its long, tense watch.

Aftermath

In the Serbian press, it was reported that a B-2 had been hit and crashed in the area of Spacvan forest, on the Croatian side, about 15 km from the Serbian border.

The fact is, there is no material evidence that anything crashed. No publicly available photos, videos, or audio recordings. However, there are strong indications that something did happen that night.

We believe that an aerial target was engaged that night, and two hits were observed.

From the air defense crew’s perspective, several key facts are clear:

The crew had no way of identifying the exact type of aircraft in the air. To them, it was simply one of many targets acquired on radar.

Can a B-2 be detected and tracked by SNR-125 fire control radar and P-18 tracking radar? As previously mentioned, the answer is yes. Although the B-2 is a large aircraft, its RCS is reportedly less than 0.1 m²—but still within the detection threshold of the SNR-125 system.

The F1 radar screen displayed a very large and very unusual radar blip. Could it have been a real aircraft? Absolutely. Could it have been a towed decoy? Possibly, but not likely, given the signature characteristics and behavior.

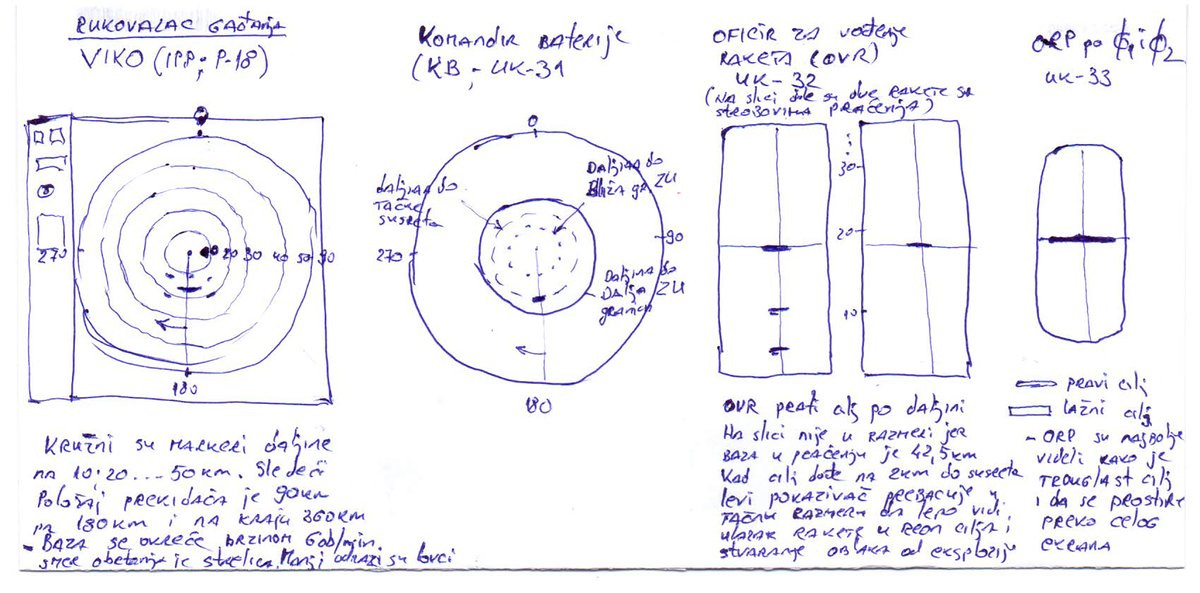

Explanation of the drawing:

Left: Shift Commander – VIKO P-18 Radar Screen

The concentric circles represent distance markers at 10, 20, …50 km intervals. The next switch position extends the range to 90 km. The radar antenna base rotates at 6 RPM. Smaller blips indicate fighter aircraft, while the larger and irregular blip likely represents a larger aircraft, possibly a stealth platform.

Mid-Left: Battery Commander – UK-31

The arrow on the left displays the distance to the interception point. The right-hand arrow indicates the nearest destruction zone, while the arrow at the bottom shows the farthest limit of the destruction zone.

Mid-Right: Missile Guidance Officers’ Screens UK-32

The left rectangular screen displays two missiles with guidance strobes. The missile guidance officer tracks the target by distance. Note that the diagram is not to scale; the tracking base is 42.5 km. As the target closes to within 2 km of the interception point, the left indicator switches to an exact scale, providing clear visibility of the missile entering the destruction zone. The resulting explosion produces a debris "cloud" that reflects electromagnetic energy.

Far Right: Manual Tracking Operators – F1 and F2 UK-33

There are two identical screens with tracking positioned at 90 degrees to each other. These operators observe the target with high precision. On this occasion, the target appeared “stretched across” the screen—something that had never been seen before.

SNR-125

The target’s altitude, speed, and flight path matched a typical evasive maneuver after a bombing mission, consistent with the behavior of an aircraft attempting to exit hostile airspace after being hit.

Immediately following the engagement, visual observers noted position lights in the sky near the Croatian border. This is highly unusual - military aircraft operating near enemy airspace rarely use position lights, suggesting a potential emergency situation.

A crash was recorded at 00:23 on the Croatian side of the border. Captain Ilija Vučković, operating a P-12 surveillance radar under the 250th Air Defense Brigade, was stationed near the village of Karlovčić. He tracked the aerial target until it disappeared from radar at a range of approximately 105 km, in the 275–280° azimuth. Notably, the Špačva Forest, located in Croatia, is roughly 100 km from Karlovčić.

Immediately after the engagement, the battalion experienced unusually fierce and coordinated attacks from multiple directions—a first for the unit, which had never faced such a synchronized aerial assault before.

Helicopter activity was reported shortly after the event, flying near but not crossing into Serbian airspace. Their presence was considered unusual and significant.

Throughout the war, radio amateurs proved to be a valuable source of information for the Serbian side. On this occasion, they reported an unusually loud noise, described as a grinding sound, followed by an explosion and a large fire on the Croatian side. These reports coincided with the radar observations and added further credibility to claims that something significant had crashed.

MORE INFORMATION CAN BE FOUND IN:

After the war

In the year after the aggression, one strange thing happened:

The annual US Air Force inventory report didn’t list Spirit of Missouri (AV-12, 88-0329). US officials claimed that it was a typo or an editorial mistake. The name of the B-2 Spirit of Missouri appeared in a later edition. Well, things like this can happen; the timing was just a bit off…

In 2005, A US delegation visited the combat crew that downed an F-117A. During the conversation, Warrant Officer Matić, F2 operator (then retired), showed them photos of the B-2 victory mark on the UNK door. Matić asked them about the downing of the B-2. The US representative was caught and simply couldn’t look Matic in the eye and answer his question. He changed the subject.

After the aggression, the US sent several questions to the Serbian military asking for very specific details about detection, in particular, B-21:

Question 1: What was the importance of the field visual observers for F-117 and B-2?

Answer: It is important to point out, as regards visual observation, that the aircraft mostly flew during the night, and the B-2 at very high altitudes, meaning that it was not visible to visual observers.

Question 2: The B-2 uses a very different refuelling system from the F-117. Have you been able to distinguish between F-117 and B-2 aerial refuelling?

Answer: Not provided in this document. The answer may well be in other documents. An aerial tanker has a large RCS; it may create a single blip on surveillance radar and the aircraft refuelling may be ‘masked’ by it. Modern radars can tell the difference.

Question 3: Where were you able to recognize and track the B-2 during flyovers of your territory?

Answer: According to our information, the B-2 took off from the USA and was escorted by fighters during air refuelling. Typical altitude was 40,000 feet, at which the aircraft can avoid our air defence. How we detected and ‘listened’ to it?… Like every other aircraft, the aircraft must report to his own command when he enters into the combat zone. Every airplane had a specific call sign, extraordinarily powerful radio, and only flew at night. The aircraft reported to flight command in Brindizi. Typically it approached from the north and fulfilled its missions north of the 45th parallel in the Belgrade zone as per defined targets such as the Chinese embassy, Interior ministry building, Defence ministry buildings, etc. We registered more than ten missions.

Question 4: Can you track the B-2, and can you identify it?

Answer: We can track targets up to 18,000 m altitude and we can identify the B-2. As previously mentioned, there is much speculation, but little direct evidence from the US side, that a B-2 was lost. But for the sake of clarity, there is evidence that something was hit that night… something really big. What was it, and did it crash or not? These are subjects for further research.

“Many ???”

It is well known that secret military projects—especially those involving stealth technology—are concealed from public view through multiple layers of classification, cover stories, and compartmentalized development. This deliberate obfuscation serves to protect national security, maintain technological advantage, and delay or prevent adversarial countermeasures. Two of the most iconic examples are the F-117 and the B-2.

The F-117 Nighthawk, the world’s first operational stealth aircraft, was developed under a highly classified program known as “Have Blue.” Its existence was not officially acknowledged by the U.S. government until 1988, five years after it had entered service. The aircraft was tested in remote desert locations like Groom Lake (commonly referred to as Area 51) under intense secrecy. To mislead observers, the F-117 was often flown only at night, leading to its “Nighthawk” nickname, and disinformation was spread to mask its capabilities and even its shape.

Similarly, the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber was developed under a black project with a veil of deception. Originally pitched during the Cold War as an "Advanced Technology Bomber" (ATB), its design, role, and budget details were hidden behind cover programs. Even after its first flight in 1989, much of its performance and internal systems remained classified for decades. The aircraft’s shape and radar-absorbing features were the result of breakthroughs in low-observable technology, which the U.S. Air Force sought to keep secret as long as possible. Budget lines for the B-2 were buried in other programs, and public discussions were often deliberately vague or misleading.

In both cases, what the public saw was only the surface of vast, complex efforts involving defense contractors, specialized government agencies, and secluded test facilities. This multilayered secrecy wasn't just for protection—it was a strategic decision to delay adversary responses, secure technological superiority, and manage political and budgetary scrutiny.

Accidents during testing and operational deployment of stealth aircraft are of utmost importance, not only due to the high cost of these platforms but also because they reveal critical information about design vulnerabilities, environmental limitations, and system reliability. For example, in 2008, a B-2 Spirit crashed shortly after takeoff from Andersen Air Force Base in Guam—the first and only loss of a B-2 to date. The cause was traced to moisture in the aircraft’s sensors, which fed incorrect data to the flight control system, resulting in an unrecoverable stall. This incident underscored how even small environmental variables can have catastrophic consequences in highly complex systems. Similarly, during the early years of the F-117 Nighthawk program, several crashes occurred, including a notable one in 1986 in California that killed the pilot. These mishaps, though shrouded in secrecy at the time, were critical in refining flight control software, pilot training protocols, and maintenance procedures. In both cases, the secrecy surrounding these aircraft often delayed public awareness of the risks and technical challenges involved. However, internally, such incidents were invaluable learning opportunities that contributed to the eventual maturity and combat readiness of stealth platforms.

What is particularly interesting about the earlier crashes is the extraordinary level of attention the USAF paid to securing and cleaning the crash sites. These locations were tightly cordoned off and heavily guarded to prevent any unauthorized access. In some cases, deception measures were employed to obscure the true nature of the wreckage and mislead observers or potential adversaries. This rigorous control over the crash sites ensured that sensitive technology did not fall into the wrong hands and helped maintain operational secrecy. Such measures reflect the strategic importance of protecting stealth technology even in the aftermath of accidents.

The crash site on the Croatian side of the border was heavily guarded from 20 May 1999 for over two months. The author had the opportunity to speak with Marijan F., a Slovenian gentleman now in his late seventies, who lives in Canada and was present in the area at the time. According to him, Croatian police strictly enforced checkpoints (even though he had a journalist ID) and did not allow anyone to pass. All roads leading toward the Spačvan Forest were blocked entirely from civilian use. Additionally, he observed SFOR vehicles and the US military trucks moving frequently throughout the area, indicating a significant and sustained security presence.

Another interesting fact is that the USAF “recycles” aircraft serial or registration numbers. For example, the numbers and marks of the airplanes are recycled. For example, F-16CG from the 555th squadron, which was downed over Yugoslavia, appeared on another F-16.

Everything is done for a reason…

Conspiracies or not?

Let’s lay out the facts that detail the early development of the B-2 Spirit strategic bomber program. The original production contract called for:

Two ground test articles – labeled AT-0998 and AT-0999 (also referred to as “Iron Birds”).

One prototype for flight testing – designated AV-1 (AT-1000)

Five pre-production aircraft – designated AV-2 to AV-6

Fifteen production aircraft - designated AV-7 to AV-21

Additionally, the contract included upgrading the five pre-series (AV-2 to AV-6) aircraft to full operational status, bringing the total to 23 aircraft, of which two were ground-based test units not intended for flight.

One of the people who participated in the tests on AT-0998 and 0999 wrote the following:

“I worked the B-2 program and remember those two aircraft very well. I worked on both. The two Stress Test birds were numbered 998 and 999. At one point, they both had hundreds of steel load cell pads glued to the outer skin. These pads were instrumented to measure stress loads during fatigue testing. After testing, they were both stored outside Bldg 435 at the Northrop facility at Plant 42 in Palmdale. They were both taken apart, and 999 and all of its parts were trucked to the Air Force Museum, where it was stored for a few years and then statically restored by the restoration crew at the Museum. They did a great job."

I talked with one of the Stress Engineers who was involved in the final fatigue test that broke the wing on 998. It broke just outboard of the radar bay at the X131 wing mate area. He said that in his estimation, the plane probably could have made it home if it had broken in flight. He said it was the strongest aircraft he had ever tested. “That thing is built like a tank. It's a great design.”

According to the “Aerial Vehicles Production List”2 webpage, up to four airframes were created either pre-production or during the early life of the airframe to test features. AV-0999 has now been on display at the USAF museum in Dayton, OH. AT 0998 is in Palmdale. Two other frames, if they can be designated as such, were used and later adapted for weapons-load trainers and testing.

When a reader carefully examines the numbers from different sources, some confusion arises, particularly regarding which airframe was actually used for testing and which one is now on display in a museum.

If the B-2 was indeed downed, it is highly unlikely that the United States would acknowledge such an event, at least not for a very long time, if ever. This is especially true if the opposing side or neutral parties lack physical evidence, such as identifiable wreckage or sensitive components, as seen with the F-117. Without undeniable proof in the public domain, official denial remains a powerful and convenient tool. The other common response is no response at all, a calculated silence, or simply feigned ignorance. In such cases, the absence of acknowledgment serves as a strategic choice, allowing officials to avoid giving the story legitimacy or traction. This tactic, often employed in sensitive military or intelligence matters, leaves just enough ambiguity to stall public scrutiny while maintaining plausible deniability.

Acknowledging the loss of such an advanced and costly strategic asset could have significant military, political, and psychological repercussions, both domestically and internationally.

The Pentagon typically does not publicly announce the loss of any aircraft during a combat mission unless the opposing side possesses material evidence, such as wreckage, captured pilots, or verifiable imagery. If an aircraft is damaged and subsequently crashes during or after the mission within "friendly territory," the official explanation is often attributed to mechanical failure or human error. In a broader sense, if a missile strike caused the damage that led to the crash, then technically, the Pentagon’s claim of mechanical failure may still hold some truth, albeit a carefully framed one. This selective framing enables plausible deniability while maintaining an internal narrative aligned with operational security goals.

A new theory

In his book The Fall of the Night Falcon, Colonel Golubović3, a former intelligence officer and member of the 3rd Battalion, presents a provocative theory that challenges the official narrative.

23 February 2008: A B-2 reportedly crashed during takeoff at Andersen Air Force Base in Guam. The official statement identified the downed aircraft as AF 89-0127, the Spirit of Kansas. Four months later, footage was released showing two B-2s taking off. The second aircraft appeared to lift off abnormally before crashing onto a grassy area near the runway. Both pilots ejected safely. This video was captured by airport surveillance cameras.

However, another video, reportedly recorded on 7 January 2011, adds an additional layer of intrigue. Filmed by base personnel close to the runway, it shows yet another angle of the failed B-2 takeoff. What’s unusual is the location from which the individuals were recording: a position where personnel are typically not permitted during takeoff procedures (at the end of the next clip, what is clearly a passenger car is visible in the crowd). This raises critical questions: Were they placed there deliberately to film the incident? Could the publication of this footage have been designed to reinforce a myth—or to support a carefully curated cover story?

It’s important to note that Andersen AFB is not a permanent base for B-2A operations. The bombers are deployed there temporarily, often as part of power-projection missions in the Pacific. This leads to a key question: How did the Spirit of Kansas come to crash there? Was it truly that aircraft—or was it a symbolic "ghost," crafted to fill a gap in public perception?

According to the official investigation, moisture condensation affected onboard sensors, causing inaccurate altitude data during takeoff. While technically plausible, this explanation only fuels further suspicion: Was this accident narrative constructed to cover a loss that actually occurred much earlier, perhaps on 20 May 1999, over Serbia?

Could it be that the real Spirit of Kansas was already gone—and had been for nine years?

Just four weeks before the crash at Andersen AFB, the base received a high-profile female visit: 15 Denver Broncos cheerleaders. Two were photographed inside the cockpit of a B-2A, specifically, the Spirit of Kansas, tail number 0127. The photo, published on Andersen AFB’s official website under the title “B-2 Pilots Support Different Kind of DV Tour,” clearly displays “0127” on the co-pilot’s seat.

This raised eyebrows. Publicly photographing a B-2A is usually governed by strict regulations, particularly regarding visible angles and markings. Yet in this case, the aircraft’s full tail number was clearly shown. Why was this permitted?

Was it intentional? Was there a need to publicly confirm that this particular aircraft, 89-0127, was active, mission-ready, and fully operational? Could it have been part of a deliberate public relations effort, intended to reaffirm the aircraft’s status just weeks before its staged “loss”?

These are the questions raised by Colonel Golubović in his book, where he suggests that this photo itself may serve as evidence—a visual anchor for a constructed legend.

According to official records, General Electric delivered more F118-GE-100 engines than were required for the production of the 21 flying B-2 bombers. This detail opens the door to a provocative possibility suggested by Golubović: that one of these surplus engines may have been installed in AT-0999, the ground test article never intended to fly.

If AT-0999 were equipped with engines and had its systems upgraded just enough, it could conceivably taxi under its own power, build up takeoff speed, and simulate a brief liftoff, ending in a controlled crash, as planned.

Golubović elaborates with a provocative claim:

“If the transport of AT-1000—AT-0999’s ‘little brother’—to the museum in 2003 worked (and it did), then we can consider that the dress rehearsal was successful. The ‘older brother’ (AT-0999) could be transferred to Guam using the same principle (since it couldn’t fly). It could be reassembled, brought to a basic operational level—just enough for it to ‘jump.’”

The implication is stunning: What if the aircraft that crashed at Andersen AFB was not the real Spirit of Kansas, but AT-0999 in disguise—used to stage a loss, reinforce a false narrative, and bury the truth about a bomber that had actually been downed years earlier over Serbia?

The next question is, could AT-0999 fly? This leads to the central technical question: Can an aircraft built exclusively for ground testing ever fly?

Logically, the answer is no. AT-0999 was never designed or certified for flight. But, as Golubović points out, “everything is possible—if it goes according to plan.”

In The Fall of the Night Falcon, he poses a string of challenging questions:

Did the crash of a B-2 on 23 February 2008 lift a burden from the hearts of those who had been carrying it since May 20, 1999?

Was this crash the perfect alibi?

Could it be that two B-2A aircraft were lost, one being the real Spirit of Kansas in 1999, and the other AT-0999 in 2008, used as its stand-in?

Was this all part of a carefully orchestrated operation to mask the downing of the world’s most expensive bomber during the war in Yugoslavia?

U.S. Air Force protocol requires wreckage from a crash to be secured and placed in a hangar for investigation. In this case, no such photos have surfaced. Only the publicly released video of the crash exists. That absence of documentation is itself suspicious.

Again, it may not seem logical, but perhaps that’s precisely the point.

Another pressing question arises: Could a B-2 loss be hidden for nine years? How could the loss of such a high-profile aircraft be hidden from over 5,000 personnel stationed at Whiteman Air Force Base?

Golubović argues that it’s entirely plausible, because of the nature of the B-2 itself. As a nuclear-capable strategic platform, access to the aircraft is highly compartmentalized. Only a small, cleared group of personnel has access to the relevant hangars, missions, and data. In such an environment, concealing the loss of a single aircraft from the broader base population is technically achievable.

As compelling as this narrative is, it must be approached with caution. Golubović himself acknowledges:

“The absence of physical wreckage or a commemorative display—such as a tail fin or wing section, which is typical in confirmed shoot-downs—prevents us from claiming with 100% certainty that a B-2A was downed by the 3rd Battalion on 20 May 1999.

Just as the downings of the F-117A and F-16CG were thoroughly documented, any assertion about a lost B-2 must be subjected to the same level of discipline, verification, and factual scrutiny.

Yet with time, new evidence—or the release of classified information—may allow future historians to either confirm or disprove this highly provocative theory. and invites deeper scrutiny of events surrounding the air war over Yugoslavia.

If AT-0999 is currently on display at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, as mentioned previously, and AT-0998 is preserved in Palmdale, then the question naturally arises: Was there an AT-0997, and could that be the mysterious airframe Colonel Golubović was referring to in his theory instead of AT-0999? The official B-2 airframe numbering system typically follows the AV (Air Vehicle) sequence, from AV-1 to AV-21. However, the “AT-099x” identifiers are less publicly documented and may refer to internal tracking codes, alternate tail numbers, or classified variants.

If AT-0997 existed—and was not acknowledged in any formal source—it’s conceivable that it represented either a prototype, a re-designated test vehicle, or even an airframe involved in a covert mishap, such as the one Colonel Golubović hints at. This opens the door to the possibility of a "phantom airframe", one whose existence and fate are obscured through paperwork, reassignments, or physical stand-ins.

Conclusion

This event carries a strong aura of conspiracy, largely because public opinion is deeply divided: some categorically dismiss any claim related to the downing of a B-2, while others are absolutely convinced that it did in fact happen.

As previously mentioned, there is no material evidence—no publicly available piece of wreckage—that definitively proves a B-2 was downed. However, there are several compelling facts and circumstantial indicators that strongly point in that direction. These clues, while not conclusive on their own, form a mosaic that cannot be easily dismissed.

Let us now elaborate on the theory of a “make-up”, a scenario in which a serious incident may have occurred but was deliberately masked through misdirection, information control, and strategic silence.

Lying is arguably more prevalent in politics and military affairs than in any other field. To simplify it, the number of lies told by politicians—when measured against the number of people employed in politics—might be the highest "per capita." Military officials are not far behind. As for intelligence operatives, deception is practically part of the job description. Presidents lie, chiefs of staff lie, members of Congress and the Senate lie—so why would the Air Force be exempt? In this world, lying is often viewed not as a moral failing, but as a tool—one that is routinely employed to achieve specific strategic or political objectives.

In many cases, the pursuit of a strategic or political objective is seen as sufficient justification for the methods employed, even if those methods involve deception or manipulation.

The theory that one of the “make-up” airframes was allegedly modified to perform only a few seconds of flight—just long enough to crash—and then be later designated as the Spirit of Kansas, serving as a cover for a B-2 lost over Serbia, is the kind of idea that sparks intense imagination. While elements of the theory are viable and raise legitimate questions, every new detail seems to open up even more uncertainties. One thing, however, is certain: the truth exists somewhere—buried beneath layers of secrecy, disinformation, and strategic silence. And whatever that truth may be, there will always be those who defend the official version and those who challenge it.

[i] Edited by Piquet (EditPiquet@gmail.com)

References

M. Mihajlović & Dj. Aničić: Shooting Down the Stealth Fighter

Bill Scot: Inside the Stealth Bomber: The B-2 Story

Thomas Whittington: B-2A Spirit Units in Combat

Steve Pace: B-2 Spirit: The Most Capable War Machine on the Planet

Jay Miller: B-2 Stealth Bomber

S. Golubović: The Fall of the Night Falcon

If you like the article (and many more articles regarding military subjects will come) you can buy me a coffee:

https://www.buymeacoffee.com/mmihajloviW

(Original paper is shown in the book: Shooting Down the Stealth Fighter)

https://b-2spirit.us/production-list/index.html

https://www.kurir.rs/vesti/drustvo/3691093/tri-teorije-o-obaranju-bombardera-b-2-na-nebu-iznda-srbije-da-li-je-zaista-nasa-pvo-srusila-najskuplji-avion-svih-vremena

Great work, Mike. Once the Aeronautical Museum in Belgrade eventually finishes with its renovations I hope to make a pilgrimage to see the remnants of that downed F-117.

Even in 2025, I reckon that America’s “stealth” aircraft like the B-2 and F-35 are by far the marquee assets in the crown of imperial soft power projection-even eclipsing their mighty aircraft carriers-and thus the proven loss of even one of these near-mystical wunderwaffens would be utterly catastrophic to their ability to intimidate rival powers.

The necessary corollary of this is that American military would do literally anything to preserve this mystique, and thus would be extremely hesitant to put them in even the slightest risk (such as the recent “B-2 strike” in Iran).

The day America’s power to project military strength dies isn’t the first supercarrier smacked by an Iranian BM, but when an F-35 meets a PL-15 for the whole world to see on PressTV or Global Times.